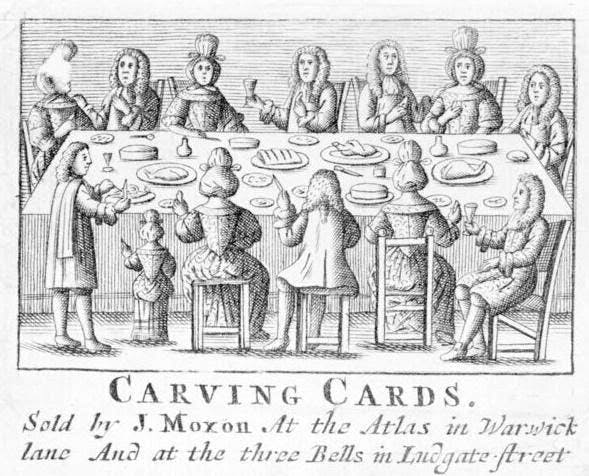

As discussed in the previous Clues, coming to Maryland in the 17th century was a gamble, with many succumbing to the diseases of the region, and all suffering from “the seasoning”. The advantages were opportunity to better your life, escape persecution, and probably unexpectedly, eating more meat. One of the important measures of the standard of living in 17th-century Europe was the amount of meat one was able to consume. This period woodcut of an elegant meal shows the numerous dishes of meat on the table, along with pies, many of which also are likely to have contained meat.

John Moxon’s Carving Cards showing an elite meal. London c. 1674

John Moxon’s Carving Cards showing an elite meal. London c. 1674

And among the most prestigious of those meats was that of deer. William the Conqueror in 1067 established New Forest and maintained earlier preserves such as the Forest of Dean in England so that deer, wild boar and certain birds would be available for hunting and consumption. Subsequent monarchs continued this practice and were avid hunters. By the 17th-century, deer could be found in the Royal Forests and in the private Deer Parks of the elite. There were three species of deer in England. The largest was the Red Deer, as can be seen in this superb painting Monarch of the Glen from 1851. Males could weight up to 530 pounds. Fallow deer were introduced by the Romans and probably again by the Normans and were smaller than the red deer, comparable in size to the American White-Tailed Deer. Roe deer were the smallest, weighing between 35 and 75 pounds. Each type is seen below.

The Monarch of the Glen (1851) A male Red Deer painted by Sir Edwin Landseer

The Monarch of the Glen (1851) A male Red Deer painted by Sir Edwin Landseer

Fallow Deer in England

Fallow Deer in England

The Roe Deer

The Roe Deer

Red and Fallow deer were the typical varieties found in the Deer Parks of the elite such as Dukes and Earls, although all were present in Royal Forests. Because of such limited availability, venison became regarded as an elite meat that was eaten by the royalty and aristocracy of England. It was similarly viewed elsewhere in Europe and few if any people of lesser status ever had the opportunity to even taste it. Venison was never sold and could only be obtained by gift. Ordinary people could only get venison by poaching it and that was severely punished. Hence, venison was viewed as a food of the nobility, or as the British would say, very posh.

I have found a few references to venison in the correspondence of George Calvert. On two occasions he wrote to the Earl of Salisbury, son of Calvert’s political mentor Robert Cecil. In a 1620 letter, he thanks the Earl for “the excellent red deer you sent” and asked if Salisbury could also “bestow a buck of this season upon my brother Mynne in Hartingfordbury.” This was the brother of Calvert’s wife Anne Mynne. In a letter of 1621 he again expresses his gratitude to Earl for another “present of venison” and in return, Calvert sent the Earl a hawk. As Secretary of State, Calvert also received a haunch of venison as a Christmas gift from the King.

Venison is a very lean meat and high in protean. It was typically cooked by boiling, roasting or baking in a pie, but first the meat was hung in a cool place for a week or more to improve the flavor. A possible venison pie recipe from 1610 is one that Anne Mynne might have used for the royal gift of venison.

To Bake a Red Deare” from The Good Huswife’s Jewel by Thomas Dawson, 1610.

“Take a handful of time, a handful of rosemarie, a handful of winter savorie, a handful of bay leaves and a handful of fennel. When your liquor seethe and you perboyle your venison in it, put in your hearbes also, and perboyle your venison until it be halfe enough. Then take it out and lay it upon a faire boorde that the water may runne out from it. Then take a knife and pricke it full of holes and while it is warme have a faire traye with vineger therein and so put your venison in from morning vntill night, and ever nowe and then turne it upside downe. Then at night have your coffin ready. This done, season it with synamome ginger, and nutmegges, pepper and salte. And when you have seasoned it, put it in your coffin and put a good quantitie of sweete butter into it. Then put it into the Oven at night when you goe to bedde. In the morning drawe it forth and put a saucer full of vineger into your pye at a hole in the toppe of it, so that the vineger may runne into everie place of it, and then stop the whole againe and turne the bottome upward. And so serve it in.”

Upon their arrival in Maryland, the settlers entered a very different environment in which deer were abundant. White-Tailed Deer were the largest animal relied upon by the Maryland Indians, providing meat, skins, glue, bone and sinew. Perhaps to symbolize their importance, tobacco pipes made by the native people and traded to the colonists were often decorated with what is called a “Running Deer” motif, as seen here. A modern picture of a deer is also given to show the similarity of the deer form with the pipe figures

Native-made tobacco pipes decorated with what are believed to be deer.

Native-made tobacco pipes decorated with what are believed to be deer.

A White-Tailed Deer standing at alert.

A White-Tailed Deer standing at alert.

Father Andrew White wrote that of “Deare there are great store”, and regarding the Yacocomico people, the English “…went daily to hunt with them for Deere and Turkies”. This was quite significant because it is unlikely that any of the settlers had ever hunted for deer before and few would have had any experience of hunting in general. Hence, the experience of hunting and eating venison was a completely new one for nearly all the colonists.

Archaeology shows that venison became a very significant element of the meat diet during the first half century of Maryland. Excavators have found hundreds of deer bones. One pit filled around 1660 at St. John’s yielded a number of deer remains including this antler from what was an eight-point buck. The antler tips or tines had been sawn off to use as knife handles, making glue or perhaps for some medicinal purpose.

Deer antler with the tines sawn off. St. John’s c. 1660.

Deer antler with the tines sawn off. St. John’s c. 1660.

Lower in the same pit came a piece of deer skull from another animal that had been sawn apart, as seen below. People do eat deer brains so that is the likely explanation for this cutting, although the brain is also used to tan deer skins in American Indian societies.

Deer Skull that had been sawn apart. From St. John’s c 1660. Photo by Donald Winter.

Deer Skull that had been sawn apart. From St. John’s c 1660. Photo by Donald Winter.

Work on the Leonard Calvert house has yielded many deer remains. One of the largest came from the fill in the ditch or moat of Pope’s Fort. It is from a male deer that was killed during the summer because the antlers were still forming and “in velvet.’

Skull and Antler from a male deer that was killed during the summer. Pope’s Fort, c. 1650. Photo by Donald Winter.

Skull and Antler from a male deer that was killed during the summer. Pope’s Fort, c. 1650. Photo by Donald Winter.

Nearly every 17th-century archaeological site I have seen in Maryland and Virginia contains deer bones. At St. John’s in the c. 1638-1665 period, up to one third of the total meat consumed came from deer. This may have been in part due to the efforts of a man called “Indian Peter.” John Lewger obtained a license to employ him as a hunter. This was a time when firearms were not widely available to Maryland Indians. We know nothing else about this individual. He may have been a Yacocomico, a Piscataway or from some other Potomac or Patuxent group. Without question, the tremendous skill of the native peoples in hunting deer derived from millennia of experience was recognized. Not only were the deer taken for meat, but the hides had a commercial value.

By the end of the 17th century, the use of deer and other wild foods declined in Maryland and Virginia, as domestic species were very prolific and readily available. Deer were still occasionally hunted but in lesser numbers. This may be due to a reduction of their populations from overhunting. Some proof of this comes from the first deer hunting regulation, passed by the legislature in 1730. It read “For the preservation for the breed of deer, no person within the province (friendly Indians exempted) shall kill any deer between the first day of January and the last day of July. Penalty, 400 pounds of tobacco—one-half to be paid to county schools and one-half to the informer” (Archives of Maryland). Additional limits were placed in the 1770s. Deer were effectively extinct in Southern Maryland by the late 19th century. Further west, commercial hunting decimated the deer populations. By 1890, most eastern states reported few if any white-tailed deer.

Restoration efforts and strict game laws in the 1920s and 30s began to re-introduce deer. Southern Maryland received animals from Western Maryland that may have come from an early 1920s replenishment in Pennsylvania. As anyone living in Maryland today knowns, those efforts meet with astonishing success. It is now necessary to control deer populations in the state through hunting and other means. And yet, except for hunters or those gifted by them, venison remains uncommon on dining tables today. Commercial sale is generally limited by healthy regulations. Such is not the case in the United Kingdom. Deer populations there also underwent a great decline but they rebounded and today are flourishing. And the British and Irish are having the same problems as we do with deer eating crops, gardens, flowers and being traffic hazards. On the other hand, they now farm raise red deer for the market. Grocery stores offer venison, and it is growing in popularity as this formally elite meat can now be consumed by the average person.

Deer in St. Mary’s. Photo courtesy of Donald Winter

Deer in St. Mary’s. Photo courtesy of Donald Winter

Coming to early Maryland had many drawbacks and required hard work and sacrifice. But one of the benefits, even for indentured servants, was consuming the meat of the aristocracy on a regular basis. Indeed, meat consumption in the colony seems to have been much higher than that in England, both in domestic and wild species. Thus, at least in terms of the meat diet, they enjoyed a higher standard of living. And being able to eat the meat of the Royals must have been a culturally significant mark of that improvement.

About the Author

Dr. Miller is a Historical Archaeologist who received a B. A. degree in Anthropology from the University of Arkansas. He subsequently received an M.A. and Ph.D. in Anthropology from Michigan State University with a specialization in historic sites archaeology. Dr. Miller began his time with HSMC in 1972 when he was hired as an archaeological excavator. Miller has spent much of his career exploring 17th-century sites and the conversion of those into public exhibits, both in galleries and as full reconstructions. In January 2020, Dr. Miller was awarded the J.C. Harrington Medal in Historical Archaeology in recognition of a lifetime of contributions to the field.